The Open Championship, often referred to as The Open or the British Open, is the oldest golf tournament in the world, and one of the most prestigious. Founded in 1860, it was originally held annually at Prestwick Golf Club in Scotland. Later the venue rotated between a select group of coastal links golf courses in the United Kingdom. It is organised by The R&A.

The Open is one of the four men’s major golf championships, the others being the Masters Tournament, the PGA Championship and the U.S. Open. Since the PGA Championship moved to May in 2019, the Open has been chronologically the fourth and final major tournament of the year. It is held in mid-July.

It is called The Open because it is in theory “open” to all, i.e. professional and amateur golfers. In practice, the current event is a professional tournament in which a small number of the world’s leading amateurs also play, by invitation or qualification. The success of the tournament has led to many other open golf tournaments to be introduced around the world.

The winner is named “the Champion Golfer of the Year”, a title that dates to the first Open in 1860, and receives the Claret Jug, a trophy first awarded in 1872.[2] The reigning champion is American Brian Harman, who won the 2023 Open at Royal Liverpool Golf Club with a score of 271.

History[edit]

Early tournament years (1860–1870)[edit]

The first Open Championship was played on 17 October 1860 at Prestwick Golf Club in Ayrshire, Scotland, over three rounds of the twelve-hole links course.[3] In the mid-19th century golf was played mainly by well-off gentlemen, as hand-crafted clubs and balls were expensive. Professionals made a living from playing for bets, caddying, ball and club making, and instruction. Allan Robertson was the most famous of these pros, and was regarded as the undisputed best golfer between 1843 and his death in 1859.[4][3] James Ogilvie Fairlie of Prestwick Golf Club decided to form a competition in 1860, “to be played for by professional golfers”,[5] and to decide who would succeed Robertson as the “Champion Golfer”. Blackheath (England), Perth, Bruntsfield (Edinburgh), Musselburgh and St Andrews golf clubs were invited to send up to three of their best players known as a “respectable caddie” to represent each of the clubs.[6] The winner received the Challenge Belt, made from red leather with a silver buckle and worth £25, which came about thanks to being donated by the Earl of Eglinton, a man with a keen interest in medieval pageantry (belts were the type of trophy that might have been competed for in archery or jousting).[7][6]

The first rule of the new golf competition was “The party winning the belt shall always leave the belt with the treasurer of the club until he produces a guarantee to the satisfaction of the above committee that the belt shall be safely kept and laid on the table at the next meeting to compete for it until it becomes the property of the winner by being won three times in succession”.[8] Eight golfers contested the event, with Willie Park, Sr. winning the championship by 2 shots from Old Tom Morris, and he was declared “The Champion Golfer of the Year”.[9][3]

A year later, it became “open” to amateurs as well as professionals. Ten professionals and eight amateurs contested the event, with Old Tom Morris winning the championship by 4 shots from Willie Park, Sr.[10][3] A prize fund (£10) was introduced in 1863 split between 2nd, 3rd and 4th (the winner only received the Challenge Belt). From 1864 onwards a cash prize was also paid to the winner.[11][12] Before this the only financial incentive was scheduling Prestwick’s own domestic tournament the same week, this allowed professionals to earn a few days’ work caddying for the wealthier gentlemen.[13] Willie Park, Sr. went on to win two more tournaments, and Old Tom Morris three more, before Young Tom Morris won three consecutive titles between 1868 and 1870. The rules stated that he was allowed to keep the belt for achieving this feat. Because no trophy was available, the tournament was not held in 1871.[3]

The introduction of course rotation and the Claret Jug (1872–1889)[edit]

On 11 September 1872 agreement was reached between Prestwick, the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers and The Royal and Ancient Golf Club. They decided that each of the three clubs would contribute £10 towards the cost of a new silver trophy, which became known as the Claret Jug, known officially as The Golf Champion Trophy, and hosting of the Open would be rotated between the three clubs. These decisions were taken too late for the trophy to be presented to the 1872 Open champion, who was once again Young Tom Morris. Instead, he was awarded with a medal inscribed ‘The Golf Champion Trophy’, although he is the first to be engraved on the Claret Jug as the 1872 winner. Medals have been given to, and kept by the winner ever since.[8] Young Tom Morris died in 1875, aged 24.[14]

The tournament continued to be dominated and won by Scottish professionals, to be rotated between the three Scottish golf courses, and played over 36 holes in a single day until 1889.[15]

English hosts and winners, and the Great Triumvirate (1890–1914)[edit]

In the 1890s, the tournament was won four times by three Englishman (two of whom were amateurs).[16] In 1892 the tournament was played for the first time at the newly built Muirfield, which replaced Musselburgh as the host venue used by the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers.[17] A few years later St George’s[18] and Royal Liverpool[19] in England were added to the rotation. From 1892 the tournament was increased in duration to four 18-hole rounds over two days[17] (Prestwick had been extended to an 18-hole course by then[20]).

Between 1898 and 1925 the tournament either had a cut after 36 holes, or a qualifying event,[21] and the largest field was 226 in 1911.[22] The large field meant sometimes the tournament was spread across up to four days.[23] In 1907 Arnaud Massy from France became the first non-British winner.[24] Royal Cinque Ports in England became the 6th different Open host course in 1909.[25]

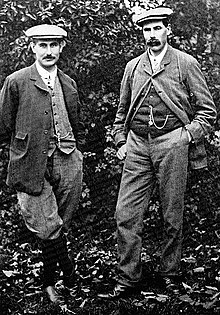

The pre-war period is most famous for the Great Triumvirate of Harry Vardon (Jersey), John Henry Taylor (England), and James Braid (Scotland). The trio combined to win The Open Championship 16 times in the 21 tournaments held between 1894 and 1914; Vardon won six times (a record that still stands today) with Braid and Taylor winning five apiece. In the five tournaments in this span the Triumvirate did not win, one or more of them finished runner-up. These rivalries enormously increased the public’s interest in golf, but the First World War meant another Open was not held until 1920, and none of the trio won another Open.[26]

American success with Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones, and the last Open at Prestwick (1920–1939)[edit]

In 1920 the Open returned, and The Royal and Ancient Golf Club became the sole organiser of the Open Championship. In 1926 they standardised the format of the tournament to spread over three days (18 holes on day 1 and 2, and 36 on day 3), and include both qualifying and a cut.[21]

In 1921 eleven U.S.-based players travelled to Scotland financed by a popular subscription called the “British Open Championship Fund”, after a campaign by the American magazine Golf Illustrated.[27] Five of these players were actually British born, and had emigrated to America to take advantage of the high demand for club professionals as the popularity of golf grew.[28] A match was played between the Americans and a team of British professionals, which is seen as a forerunner of the Ryder Cup.[29] When the Open was held two weeks later, one of these visitors, Jock Hutchison, a naturalised American citizen, won in St Andrews, the town of his birth.[30]

In 1922 Walter Hagen won the first of his four Opens, and become the first American-born winner. The period between 1923 and 1933 saw an American-based player win every year (two were British-born), and included three wins by amateur Bobby Jones, and one by Gene Sarazen, who had already won top tournaments in the United States. English players won every year between 1934 and 1939, including two wins by Henry Cotton (he would go on to win a third in 1948).[3]

After overcrowding issues at the 1925 Open at Prestwick, it was decided it was no longer suitable for the growing size of the event, being too short, having too many blind shots, and it could not cope with the volume of spectators.[31] The Open’s original venue was replaced on the rota with Carnoustie,[32] which hosted for the first time in 1931. Troon hosted for the first time in 1923,[33] and Royal Lytham & St Annes was also added, hosting for the first time in 1926.[34] Prince’s hosted its one and only Open in 1932.[35]

Bobby Locke, Peter Thomson, and Ben Hogan’s Triple Crown (1946–1958)[edit]

The Open returned after the Second World War to St Andrews, with a victory for American Sam Snead. Bobby Locke became the first South African winner, winning three times in four years between 1949 and 1952, and later winning a fourth title in 1957. Having already won the Masters and the U.S. Open earlier in the year, Ben Hogan won in his one and only Open appearance in 1953 to win the “Triple Crown”.[3] His achievement was so well regarded he returned to New York City to a ticker-tape parade.[36] Peter Thomson became the first Australian winner, winning four times in five years between 1954 and 1958, and later winning a fifth title in 1965.[3] After flooding prevented Royal Cinque Ports from hosting, both in 1938 and 1949, it was removed from the rota.[37] The Open was played outside of England and Scotland for the first time in 1951 at Royal Portrush, Northern Ireland.[38]

The period saw fewer American entrants, as the PGA Tour had grown to be quite lucrative, and the PGA Championship was often played at the same or similar time paying triple the prize money.[39][40] A larger golf ball was also used in America, which meant they had to adjust for the Open.[41]

Player, Palmer, Nicklaus – The Big Three (1959–1974)[edit]

In 1959, Gary Player, a young South African, won the first of his three Opens. Only four Americans had entered, but in 1960 Arnold Palmer travelled to Scotland after winning the Masters and U.S. Open, in an attempt to emulate Hogan’s 1953 feat of winning all three tournaments in a single year. Although he finished second to Kel Nagle, he returned and won the Open in 1961 and 1962. Palmer was hugely popular in America, and his victories are likely to have been the first time many Americans would have seen the Open on television. This, along with the growth of trans-Atlantic jet travel, inspired many more Americans to travel in the future.[3]

The period is primarily defined by the competition between Player, Palmer, and Jack Nicklaus. Nicklaus won three times (1966, 1970, 1978) and had a record seven runner-ups. American Lee Trevino also made his mark winning his two Opens back to back in 1971 and 1972, the latter denying Nicklaus a calendar year Grand Slam.[3] The only British champion in this period was Tony Jacklin,[42] and it is also notable for having the first winner from Argentina, Roberto De Vicenzo.[43]

Watson, Ballesteros, Faldo, and Norman (1975–1993)[edit]

By 1975, the concept of the modern majors had been firmly established, and the PGA Championship had been moved to August since 1969,[40] so no longer clashed with the Open. This meant the Open had a feel similar to the current tournament, with the leaders after 36 holes going off last (1957 onwards),[44] all players having to use the “bigger ball” (1974 onwards),[45][46][47] play spread over four days (1966 onwards, although the days were Wednesday to Saturday until 1980),[48][49] and a field containing all the world’s best players.

American Tom Watson won in 1975. Turnberry hosted for the first time in 1977, and Watson won the Open for the second time, after one of the most celebrated contests in golf history, when his duel with Jack Nicklaus went to the final shot before Watson emerged as the champion. He would go on to win again in 1980, 1982 and 1983, to win 5 times overall,[3] a record only bettered by Harry Vardon, and he became regarded as one of the greatest links golf players of all time.[50]

In 1976, 19-year-old Spaniard Seve Ballesteros gained attention in the golfing world when he finished second.[51] He would go on to win three Opens (1979, 1984, 1988), and was the first continental European to win since Arnaud Massy in 1907. Other multiple winners in this period were Englishman Nick Faldo with three (1987, 1990, 1992), and Australian Greg Norman with two (1986, 1993).[3]

Tiger Woods and the modern era (1994 onwards)[edit]

Every year between 1994 and 2004 had a first-time winner.[52] In 1999, the Open at Carnoustie was famously difficult, and Frenchman Jean van de Velde had a three-shot lead teeing off on the final hole. He ended up triple bogeying after finding the Barry Burn, and Scotman Paul Lawrie, ranked 241st in the world, ended up winning in a playoff. He was 10 strokes behind the leader going into the final round, a record for all majors.[53] He was not the only unheralded champion during this span, as 396th-ranked Ben Curtis[54] and 56th-ranked Todd Hamilton[55] won in 2003 and 2004, respectively.

In 2000, Tiger Woods, having just won the U.S. Open, became champion by a post-war record 8 strokes[56] to become the youngest player to win the career Grand Slam at age 24.[3] After winning the 2002 Masters and U.S. Open, he became the latest American to try to emulate Ben Hogan and win the Open in the same year. His bid came to a halt on Saturday with the worst round of his career up to that time, an 81 (+10) in cold, gusty rain.[57] He went on to win again back-to-back in 2005 and 2006 to bring his total to three wins. Other multiple winners in this era are South African Ernie Els (2002, 2012) and Irishman Pádraig Harrington (2007, 2008).[3][52]

In 2009, 59-year-old Tom Watson led the tournament through 71 holes and needed just a par on the last hole to become the oldest ever winner of a major championship, and also match Harry Vardon‘s six Opens. Watson bogeyed, setting up a four-hole playoff, which he lost to Stewart Cink.[58] In 2015, Jordan Spieth became another American to arrive having already won the year’s Masters and U.S. Open tournaments. He finished tied for fourth as Zach Johnson became champion.[59] Spieth would go on to win the 2017 Open at Royal Birkdale.[52]

American Phil Mickelson won his first Open, and fifth major, in 2013.[52] In 2016, he was involved in an epic duel with Sweden’s Henrik Stenson, which many people compared to the 1977 Duel in the Sun between Jack Nicklaus and Tom Watson. Stenson emerged the winner, and the first Scandinavian winner of a male professional major championship, with a record Open (and major) score of 264 (−20), three shots ahead of Mickelson, and 14 shots ahead of third place. Jack Nicklaus shared his thoughts on the final round, saying: “Phil Mickelson played one of the best rounds I have ever seen played in the Open and Henrik Stenson just played better—he played one of the greatest rounds I have ever seen”.[60][61]

Francesco Molinari won the 2018 Open at Carnoustie by two shots, to become the first Italian major winner.[62] Shane Lowry won the 2019 Open when the tournament returned to Royal Portrush Golf Club, to become the second champion from the Republic of Ireland.[63]

In 2020, the Open Championship was cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was the first time the championship had been cancelled since World War II. The R&A also confirmed that Royal St George’s, which would have hosted the championship in 2020, would be the host venue in 2021, effectively retaining the Old Course at St Andrews as the venue for the 150th Open.[64]

Traditions[edit]

Links golf course[edit]

The Open is always played on a coastal links golf course. Links golf is often described as the “purest” form of golf and keeps a connection with the way the game originated in Scotland in the 15th century. The terrain is open, often without any trees, and will generally be undulating with a sandy base. The golf courses are often primarily shaped by nature, rather than ‘built’. Weather, particularly wind, plays an important role, and although there will be a prevailing onshore breeze, changes in the wind direction and strength over the course of the tournament can mean each round of golf has to be played slightly differently. The courses are also famous for deep pot bunkers, and gorse bushes that make up the “rough”. A golfer playing on a links course will often adapt his game so the flight of the ball is lower and so is less impacted by the wind, but this will make distance control more difficult. Also due to the windy conditions the speed of the greens are often slower than a golfer might be used to on the PGA Tour, to avoid the ball being moved by a gust.[65][66]

Old Course at St Andrews[edit]

The Old Course at St Andrews is regarded as the oldest golf course in the world, and winning the Open there is widely considered to be one of the pinnacles of achievement in golf.[67] Given the special status of the Old Course, the Open is generally played there once every five years in the modern era, much more frequently than the other courses used for the Open.[68]

Previous champions will often choose St Andrews as their final Open tournament. It has become traditional to come down the 18th fairway to huge applause from the amphitheatre crowds, and to pose for final pictures on the Swilken Bridge with the picturesque clubhouse and town in the background.[69]

Trophy presentation[edit]

The Open trophy is the Claret Jug, which has been presented to the champion since 1873 (it was first awarded to Young Tom Morris in 1872, however the trophy was not ready in time—his name is the first to be engraved on it).[2] The original trophy permanently resides on display in the R&A’s Clubhouse at St Andrews. Therefore, the trophy that is presented at each Open is a replica which is retained by the winner for a year. It used to be the responsibility of the winner to get his name engraved on the trophy, but 1967 winner Roberto De Vicenzo returned the trophy without having done so.[70] Subsequently, the winner’s name is already engraved on it when presented, which often results in television commentators speculating as to when it is safe for the engraver to start.[71]

“You know to have dreams, to have things that you think are unattainable, if you give up on them, what’s left? I am immensely proud my name is on that Claret Jug.”

—2011 Open winner Darren Clarke on fulfilling a lifelong ambition.[72]

The winner of the Open is announced as “The Champion Golfer of the Year”, a title which has been used since the first Open in 1860.[2] He will nearly always pose for photos with the trophy sitting on one of the distinctive pot bunkers.[73] Three-time winner Jack Nicklaus said holding the Claret Jug was like holding “a newborn baby”, and on other players putting champagne or other drinks inside it to celebrate their Open win, he said “I never used the Claret Jug for anything other than what it symbolized – Champion Golfer of the Year.”[74]

Name[edit]

The first event was held as an invitational tournament, but the next year Prestwick Golf Club declared that “the belt… on all future occasions, shall be open to all the world”.[75] In its early years it was often referred to as The Championship but with the advent of the Amateur Championship in 1885, it became more common to refer to it as The Open Championship or simply The Open. The tournament inspired other national bodies to introduce open golf tournaments of their own, such as the U.S. Open, and later many others.[76] To distinguish it from their own national open, it became common in many countries to refer to the tournament as the “British Open”. The R&A (the tournament’s organiser) continued to refer to it as The Open Championship. During the interwar years, a period with many U.S.-based winners, the term British Open would occasionally be used during the trophy presentation and in British newspapers.[77][78]

In 2017, a representative of the R&A openly stated that it is a priority to “eradicate the term British Open” and have a single identity and brand of “The Open” in all countries.[79] Tournament partners, such as the PGA Tour, now refer to it without “British” in the title,[80] media rightsholders are contractually required to refer to the event as The Open Championship,[79] and the official website has released a statement titled “Why it’s called ‘The Open’ and not the ‘British Open'” stating that “The Open is the correct name for the Championship. It is also the most appropriate”.[76] The R&A’s stance has attracted criticism from some commentators.[79][81][82]

The R&A also run The Senior Open, the over 50s equivalent of the Open, which was officially known as the “Senior British Open” from its inception in 1987 until 2007, when “British” was dropped from the name.[83] The Women’s Open, seen by some as the women’s equivalent to the Open (although unlike the Open it is not always held on a links course, and was not run by the R&A until 2017) was officially known as the “Women’s British Open” from its inception in 1976 until 2020, when the word “British” was dropped from the name as part of a sponsorship deal with AIG.[84]

Status[edit]

The Open is recognised as one of the four major championships in golf, and is an official event on the PGA Tour, European Tour, and the Japan Golf Tour.

The Open began in 1860, and for many years it was not the most-followed event in golf, as challenge matches between top golfers were more keenly followed and drew larger crowds.[85] The Great Triumvirate dominated the Open between 1894 and 1914 and were primarily responsible for the formation of the PGA in 1901 which had a big impact in promoting interest in professional golf (and therefore The Open) and increasing playing standards.[86] Between the World Wars, the first wins by Americans were widely celebrated when they broke the dominance previously held by British players.[87] After World War II, although the profile of the tournament remained high in the UK and Commonwealth countries, the low prize money compared to the US events and the cost of travel meant fewer Americans participated. High-profile visits and wins by Ben Hogan and Arnold Palmer, the growth of cheaper and faster transatlantic flights, and the introduction of television coverage recovered its prestige.[3]

When the modern concept of the majors was cemented, the Open was included as one of those four. Thus, the Open is now one of the four majors in golf, along with the U.S. Open, PGA Championship, and Masters Tournament. The term “major” is a universally-acknowledged unofficial term used by players, the media, and golf followers to define the most important tournaments, and performance in them is often used to define the careers of the best golfers.[88] There is often discussion amongst the golfing community as to whether the Open, U.S. Open, or the Masters Tournament is the most prestigious major, but opinion varies (often linked to nationality). The PGA Championship is usually seen as the least prestigious of the four.[89][90]

In terms of official recognition, the tournament has been an event on the European Tour since its formation in 1972. In 1995, prize money won in the Open was included in the PGA Tour official money list for the first time, a change that caused an increase in the number of American entries.[91] In addition all previous PGA Tour seasons have been retroactively adjusted to include the Open in official money and win statistics. Currently the Open, along with the other three majors and The Players Championship, are the top-tier tournaments in the PGA Tour’s FedEx Cup, offering more points than any other non-playoff event. The Open is also an official event on the Japan Golf Tour.[92]

Structure[edit]

See also: The Open Championship format and qualification

Qualifying[edit]

See also: Qualifying process

Qualifying was introduced in 1907, and for much of its history, all players had to go through the qualification process. In the modern era, the majority of players get an exemption from qualification which is awarded for previous performance in the Open, performance in high-profile global tournaments (such as other majors), performance in top golf tours, or a high position in the Official World Golf Ranking (OWGR). Five amateurs are also exempt from qualifying by winning various global amateur titles provided they maintain their amateur status prior to The Open.[93]

Another way of qualifying is to finish in a high position in the Open Qualifying Series of global events, which are about twelve tour events across the globe, run by various local golfing organisations.[94]

Any male professional golfer, male amateur golfer whose playing handicap does not exceed 0.4 (i.e. scratch) or has been within World Amateur Golf Ranking listing 1–2,000 during the current calendar year, and any female golfer who finished in the top 5 and ties in the latest edition of any of the five women’s majors is eligible to enter local qualifying. If they perform well they will go on to Final Qualifying, which is four simultaneous 36-hole one-day events held across the UK, with 12 players qualifying for the Open.[94] If there are any spots left, then alternates are made up from the highest ranked players in the OWGR who are not already qualified, which brings the total field up to 156 players.[95]

In 2018, the OWGR gave the Open a strength of field rating of 902 (the maximum possible is 1000 if the top 200 players in the world were all in a tournament). This was only bettered by the PGA Championship, a tournament which actively targets a high strength of field rating.[96][97]

Format[edit]

Field: 156 players[98]

Basic Format: 72 hole stroke play. Play 18 holes a day over four days, weather permitting.[98]

Date of Tournament: starts on the day before the third Friday in July.[99]

Tournament Days: Thursday to Sunday.[98]

Tee off times: each player has one morning and one afternoon tee time in first two days in groups of three, which are mostly randomised (with some organiser discretion). Groupings of two on the last two days with last place going off first and leaders going out last.[100]

Cut: after 36 holes, only top 70 and ties play the final 36 holes.[98]

Playoff: if there is a tie for the lead after 72 holes, a three-hole aggregate playoff is held; followed by sudden death if the lead is still tied.[101]

Prizes[edit]

Up until 2016, the purse was always stated, and paid, in pounds sterling (£), but was changed in 2017 to US dollars ($) in recognition of the fact that it is the most widely adopted currency for prize money in golf.[102]

Champion’s prizes and benefits[edit]

The champion receives trophies, the winner’s prize money, and several exemptions from world golf tours and tournaments. He is also likely to receive a winner’s bonus from his sponsors.[103] The prizes and privileges on offer for the champion included:

- The Golf Champion Trophy (commonly known as the Claret Jug). The winner keeps the trophy until the next Open, at which point it must be returned, and a replica is provided as a replacement.[104][105]

- The winner’s gold medal (originally awarded in 1872 when the Claret Jug was not yet ready, and since awarded to all champions).[104][105]

- If the winner is a professional, then the winner’s share (18%) of the purse.[106]

- Guaranteed entry to all future Open Championships until the age of 60, and entry to the next ten Opens, even if over the age of 60.[107]

- Entry to the next five editions of the Masters Tournament, PGA Championship, and U.S. Open.[104]

- Five year membership to the PGA Tour and the European Tour.[104][108]

- Entry to the next edition of the WGC-HSBC Champions.[109]

- Entry to the next five editions of The Players Championship, and the five invitational tournaments (Genesis Invitational, Fort Worth Invitational, the Arnold Palmer Invitational, the RBC Heritage, and the Memorial Tournament) on the PGA Tour.[110]

- Automatic invitations to three of the five senior majors once they turn 50; they receive a one-year invitation to the U.S. Senior Open and a lifetime invitation to the Senior PGA Championship and Senior Open Championship.[111][112][113]

- FedEx Cup, Race to Dubai, Ryder Cup/Presidents Cup, and Official World Golf Ranking points.[104]

From 1860 to 1870, the winner received the challenge belt. When this was awarded to Young Tom Morris permanently for winning three consecutive tournaments, it was replaced by the gold medal (1872 onwards), and the Claret Jug (1873 onwards).[105]

Other prizes and benefits, based upon finishing position[edit]

There are several benefits from being placed highly in the Open. These are:

- The runners up each receive a silver salver.[114]

- If the player is a professional, then a share of the purse. There is a distribution curve for those who make the cut, with 1st place getting 18%, 2nd 10.4%, 3rd 6.7%, 4th 5.2%, and 5th 4.2%. The percentage continues to fall by placing with 21st getting 1% and 37th 0.5%. Professionals who miss the cut received between US$7,375 and US$4,950.[106]

- The top 10 players, including ties, get entry to the next edition of The Open Championship.[107]

- The top 4 players, including ties, get entry to the next edition of the Masters Tournament.[115]

- FedEx Cup, Race to Dubai, Ryder Cup/Presidents Cup, and Official World Golf Ranking points.[104]

Amateur medals[edit]

Since 1949 the leading amateur completing the final round receives a silver medal. Since 1972, any other amateur who competes in the final round receives a bronze medal.[105] Amateurs do not receive prize money.[116]

Professional Golfers’ Association (of Great Britain and Ireland) awards[edit]

The Professional Golfers’ Association (of Great Britain and Ireland) also mark the achievements of their own members in The Open.

- Ryle Memorial Medal – awarded since 1901 to the winner if he is a PGA member.[117][118]

- Braid Taylor Memorial Medal – awarded since 1966 to the highest finishing PGA member.[117][119]

- Tooting Bec Cup – awarded since 1924 to the PGA member who records the lowest single round during the championship.[117][120]

The Braid Taylor Memorial Medal and the Tooting Bec Cup are restricted to members born in, or with a parent or parents born in, the United Kingdom or Republic of Ireland.[104]

Courses[edit]

See also: List of The Open Championship venues

The Open Championship has always been held on a coastal links golf course in Scotland, England or Northern Ireland. The hosting pattern has been:[68]

- 1860–1870: Prestwick Golf Club is the sole host.

- 1872–1892: three-year rotation among Prestwick, St Andrews, and Musselburgh (replaced by Muirfield in 1892) golf clubs.

- 1893–1907: five-year rotation among Prestwick, Royal St George’s, St Andrews, Muirfield, and Royal Liverpool Golf Clubs.[121][122]

- 1908–1939: six-year rotation, initially among Prestwick, Royal Cinque Ports, St Andrews, Royal St George’s, Muirfield, and Royal Liverpool Golf Clubs, thus alternating between Scotland and England.[123][124] A few changes were made to the rota of 6 courses after World War I.

- 1946–1972: alternating between Scottish and English golf clubs continues, but without a fixed rota. Exceptions were St Andrews hosting pre- and post-World War II, and Northern Ireland hosting in 1951.

- Since 1973: usually three Scottish and two English courses hosting in a five-year period, mostly alternating between the two countries, with St Andrews hosting about every five years. Northern Ireland returned in 2019.[125]

Overview[edit]

A total of 14 courses have hosted the Open, with ten currently active as part of the rotation, and four have been retired from the rotation (shown in italics). The year the golf course was originally built is shown in parentheses.

Prestwick Golf Club (1851):[126] Prestwick is The Open’s original venue, and hosted 24 Opens in all, including the first 12.[68] Old Tom Morris designed the original 12 hole course,[126] but it was subsequently redesigned and expanded to be an 18-hole course in 1882.[127] Serious overcrowding problems at Prestwick in 1925 meant that the course was never again used for the Open, and was replaced by Carnoustie Golf Links as the third Scottish course.[31][32]

Old Course at St Andrews (1552):[128] considered the oldest golf course in the world, and referred to as “the home of golf”.[129] In 1764, the Society of St Andrews Golfers reduced the course from 22 to 18 holes and created what became the standard round of golf throughout the world.[130] Famous features include the “Hell Bunker” (14th) and the Road Hole (17th).[131] Due to its special status St Andrews usually hosts the Open every five years in the modern era.[68] It is designed to be played in wind, so can result in low scores in benign conditions.[132]

Musselburgh Links (c. 1672):[128] a 9-hole course that hosted six Opens as it was used by the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers, one of the organisers of The Open between 1872 and 1920. When the Honourable Company built their own course in 1891 (Muirfield), it took over hosting duties.[133] Musselburgh was unhappy with this and organised another rival ‘Open‘ competition prior to the Muirfield event, one with greater prize money.[134]

Muirfield (1891): built by the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers to replace Musselburgh on the rota. Known for the circular arrangement the course has, which means the wind direction on each hole changes, and can make it tricky to navigate.[135] Briefly removed from the rota in 2016–17 due to not having any female members.[136][137]

Royal St George’s Golf Club (1887):[138] often simply referred to as Sandwich. The first venue to host in England, and the only venue on the current rota in Southern England. It went 32 years without hosting between 1949 and 1981, but returned following the rebuilding of three holes, tee changes to another two holes, and improved road links.[139] Known for having the deepest bunker on the rota (4th hole).[140]

Royal Liverpool Golf Club (1869):[141] often simply referred to as Hoylake. Royal Liverpool went 39 years without hosting between 1967 and 2006,[68] but returned following changes to tees, bunkers, and greens.[141] In 2006, Tiger Woods won by using his driver just once.[142]

Royal Cinque Ports Golf Club (1892):[143] hosted the 1909 and 1920 Opens, and was scheduled to host in 1938 and 1949 but both had to be moved to Royal St George’s Golf Club due to abnormally high tides flooding the course. It was removed from the rota but is still used for qualifying.[144][145][146][147][148]

Royal Troon Golf Club (1878):[149] first used in 1923 instead of Muirfield when “some doubts exists as to the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers being desirous of their course being used for the event”.[150] Redesigned, lengthened, and strengthened by James Braid shortly before it held its first Open. Famous features include the “Postage Stamp” 8th hole, and the 601 yards 6th.[149]

Royal Lytham & St Annes Golf Club (1886):[151] a relatively short course, but has 167 bunkers which demand accuracy.[152] Slightly inland as some coastal homes have been built since the course first opened.[151]

Carnoustie Golf Links (1835):[128] replaced Prestwick after https://webbworth.com/ it was no longer suitable for the Open.[32] It went through modifications prior to the 1999 Open. Thought of as being the toughest of the Open venues, especially the last three holes, and is well remembered for Jean van de Velde triple bogeying on the 18th when he only needed a double bogey to win.[53]

Prince’s Golf Club (1906): only hosted once in 1932. Has been redesigned in 1950 due to war damage.[153]

Royal Portrush Golf Club (1888):[154] the only venue to host the Open outside England and Scotland when it hosted in 1951. With the Troubles in Northern Ireland significantly diminished since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, and after the successful hosting of the Irish Open it returned as host in 2019. The course underwent significant changes before the 2019 Open, including replacing the 17th and 18th holes, which also provided the space for spectators and corporate hospitality that a modern major requires.[125]

Royal Birkdale Golf Club (1894): extensively redesigned by Fred Hawtree and JH Taylor to create the current layout in 1922, it is known for its sand dunes towering the fairways. Often ranked as England’s best Open venue.[155][156][157]

Turnberry (1906): made its Open debut in 1977, when Tom Watson and Jack Nicklaus famously played the Duel in the Sun. Known to be one of the most picturesque Open venues, it was bought by Donald Trump in 2014, who has spent substantial amounts renovating the course.[158] On 11 January 2021, in the aftermath of the 2021 United States Capitol attack the week prior, the R&A announced that it will not stage a championship at Turnberry “in the foreseeable future”.[159][160]

Hosting record of each course[edit]

Future venues[edit]

| Year | Edition | Course | Town | County | Country | Dates | Last hosted | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 152nd | Royal Troon Golf Club | Troon | South Ayrshire | Scotland | 18–21 July | 2016 | [161] |

| 2025 | 153rd | Royal Portrush Golf Club | Portrush | Antrim | Northern Ireland | 17–20 July | 2019 | [162] |

| 2026 | 154th | Royal Birkdale Golf Club | Southport | Merseyside | England | 16–19 July | 2017 | [163] |

Records[edit]

- Oldest winner: Old Tom Morris (46 years, 102 days), 1867.

- Youngest winner: Young Tom Morris (17 years, 156 days), 1868.[164]

- Most victories: 6, Harry Vardon (1896, 1898, 1899, 1903, 1911, 1914).

- Most consecutive victories: 4, Young Tom Morris (1868, 1869, 1870, 1872 – there was no championship in 1871).

- Lowest score after 36 holes: 129, Louis Oosthuizen (64-65), 2021.

- Lowest score after 54 holes: 197, Shane Lowry (67-67-63), 2019.

- Lowest final score (72 holes): 264, Henrik Stenson (68-65-68-63), 2016.

- Lowest final score (72 holes) in relation to par: −20, Henrik Stenson (68-65-68-63=264), 2016; Cameron Smith (67-64-73-64=268), 2022.

- Greatest victory margin: 13 strokes, Old Tom Morris, 1862. This remained a record for all majors until 2000, when Woods won the U.S. Open by 15 strokes at Pebble Beach. Old Tom’s 13-stroke margin was achieved over 36 holes.

- Lowest round: 62, Branden Grace, 3rd round, 2017; a record for all majors.

- Lowest round in relation to par: −9, Paul Broadhurst, 3rd round, 1990; Rory McIlroy, 1st round, 2010.

- Wire-to-wire winners (after 72 holes with no ties after rounds): Ted Ray in 1912, Bobby Jones in 1927, Gene Sarazen in 1932, Henry Cotton in 1934, Tom Weiskopf in 1973, Tiger Woods in 2005, and Rory McIlroy in 2014.[165]

- Most runner-up finishes: 7, Jack Nicklaus (1964, 1967, 1968, 1972, 1976, 1977, 1979).

Winners[edit]

See also: List of The Open Championship champions

Nationalities assigned above match those used in the official Open records. Source: The 148th Open 2019 Media Guide[169]

Silver Medal winners[edit]

Since 1949, the silver medal is awarded to the leading amateur, provided that the player completes all 72 holes.[105] In the earlier years wealthy individuals would often maintain their amateur status, and hence could win multiple times, such as Frank Stranahan who won it four times in the first five years (and was also the low amateur in 1947). In the modern era players often turn professional soon after winning the silver medal, and hence never have a chance for multiple wins. Tiger Woods and Rory McIlroy are the only silver medal winners who have gone on to win the Open.

- 1949 – Frank Stranahan

- 1950 – Frank Stranahan (2)

- 1951 – Frank Stranahan (3)

- 1952 – Jackie Jones

- 1953 – Frank Stranahan (4)

- 1954 – Peter Toogood

- 1955 – Joe Conrad

- 1956 – Joe Carr

- 1957 – Dickson Smith

- 1958 – Joe Carr (2)

- 1959 – Reid Jack

- 1960 – Guy Wolstenholme

- 1961 – Ronnie White

- 1962 – Charlie Green

- 1963 – none

- 1964 – none

- 1965 – Michael Burgess

- 1966 – Ronnie Shade

- 1967 – none

- 1968 – Michael Bonallack

- 1969 – Peter Tupling

- 1970 – Steve Melnyk

- 1971 – Michael Bonallack (2)

- 1972 – none

- 1973 – Danny Edwards

- 1974 – none

- 1975 – none

- 1976 – none

- 1977 – none

- 1978 – Peter McEvoy

- 1979 – Peter McEvoy (2)

- 1980 – Jay Sigel

- 1981 – Hal Sutton

- 1982 – Malcolm Lewis

- 1983 – none

- 1984 – none

- 1985 – José María Olazábal

- 1986 – none

- 1987 – Paul Mayo

- 1988 – Paul Broadhurst

- 1989 – Russell Claydon

- 1990 – none

- 1991 – Jim Payne

- 1992 – Daren Lee

- 1993 – Iain Pyman

- 1994 – Warren Bennett

- 1995 – Steve Webster

- 1996 – Tiger Woods

- 1997 – Barclay Howard

- 1998 – Justin Rose

- 1999 – none

- 2000 – none

- 2001 – David Dixon

- 2002 – none

- 2003 – none

- 2004 – Stuart Wilson

- 2005 – Lloyd Saltman

- 2006 – Marius Thorp

- 2007 – Rory McIlroy

- 2008 – Chris Wood

- 2009 – Matteo Manassero

- 2010 – Jin Jeong

- 2011 – Tom Lewis

- 2012 – none

- 2013 – Matt Fitzpatrick

- 2014 – none

- 2015 – Jordan Niebrugge

- 2016 – none

- 2017 – Alfie Plant

- 2018 – Sam Locke

- 2019 – none

- 2020 – no tournament

- 2021 – Matti Schmid

- 2022 – Filippo Celli

- 2023 – Christo Lamprecht

Broadcasting[edit]

Further information: List of The Open Championship broadcasters

The distribution of The Open is provided by a partnership between R&A Productions, European Tour Productions (both run by IMG) and CTV Outside Broadcasting. The broadcasters with onsite production are Sky (UK), NBC (USA), BBC (UK), and TV Asahi (Japan).[170]

Many non-British broadcasters referred to the Open as the “British” Open in their coverage until 2010, when The R&A introduced use of contractual terms in their media contracts, similar to the Masters, and now rights holders are obliged to refer to the tournament as “The Open”.[79] On 7 November 2018, the parent company of the U.S. rights holder, NBC, completed a takeover of the U.K. rights holder, Sky. This means the media rights in the two primary markets are owned by the same company, albeit produced separately by two different subsidiaries.[171] There are over 170 cameras on site during the tournament, including cameras in the face of the Open’s pot bunkers.[172][173]

Ivor Robson was the announcer for 41 years; he died in October 2023.[174]

United Kingdom[edit]

The BBC first started to broadcast the Open in 1955,[175] with Peter Alliss involved since 1961, and having the role of lead commentator since 1978.[176] With the growth of pay television, and the increasing value of sporting rights, the BBC’s golf portfolio began to reduce. The loss of the rights to the Scottish Open, and BMW PGA Championship in 2012 left the BBC’s only golf coverage as the Open, and the final two days of the Masters (which it shared with Sky). With so little golf, the BBC was accused of neglecting investment in production and was criticised about its ‘quality of coverage and innovation’ compared to Sky, which held the rights to most golf events. The tournament is considered a Category B event under the Ofcom Code on Sports and Other Listed and Designated Events, which allows its rights to be held by a pay television broadcaster as long as sufficient secondary coverage is provided by a free-to-air broadcaster.[177][175][178]

Many were hoping that a deal similar to the Masters would be reached, where Sky had coverage of all four days, and the BBC also provided live weekend coverage, but Sky were not keen on this and won the full rights in 2015. Some were angered about the demise of golf on terrestrial television, and the impact that could have on the interest in golf in the U.K.,[179][180] whilst others were pleased about the perceived improved coverage that Sky would give.[181] Despite Peter Alliss promising on air that the BBC would cover the 2016 event, the BBC reached a deal for Sky to take the coverage. The BBC still covers the tournament, showing highlights from 8pm–10pm on tournament days and radio coverage on Radio 5 Live. The deal with Sky required the broadcaster to restrict its advertisement breaks to 4 minutes every hour, similar to the Masters.[181] Sky also offers complete coverage online through NOW to non-subscribers, which is £7.99 for one day, or £12.99 for a weeks access.[182]

Timeline of U.K. broadcasting rights[edit]

| Period | Broadcaster | Rights fee per annum |

|---|---|---|

| 1955–2014 | BBC | Varies |

| 2015 | £7.0m | |

| 2016[k] | Sky Sports | £7.0m[k] |

| 2017–2021 | £15.0m | |

| 2022–2024 | Unknown |

United States[edit]

ABC began broadcasting the Open in 1962, with taped highlights on Wide World of Sports.[186] In the pre-digital age the coverage had to be converted from the U.K.’s PAL colour encoding system, to the U.S.’s NTSC, which meant picture quality could be impacted, especially in the early years.[187] The coverage expanded over the years, and as is common in America, there was a different early round rights holder, which was ESPN until 2003 when TNT took over. Co-owned ESPN became responsible for ABC’s sports coverage in 2006; it won the rights to cover all four days of the championship in 2010, and concurrently moved coverage to its channels. The Open became the first golf major to be covered exclusively on pay television in America, as ESPN left only highlights for its partner broadcast network.

After losing the rights to the U.S. Open in 2015, NBC bid aggressively to win the rights to the Open, and become a broadcaster of a golf major again.[186] NBC also had a track record of broadcasting European sporting events successfully in the morning U.S. time with the Premier League, Formula One, and “Breakfast at Wimbledon”, and was able to place early round coverage on its subsidiary Golf Channel.[188][189] NBC won the rights from 2017 to 2028.[190][173] ESPN also sold them the rights for 2016.[191]

The 2019 edition of the Open Championship had a total of 49 hours of coverage in the United States, with 29 hours being on Thursday and Friday, and 20 hours being on Saturday and Sunday; the Golf Channel cable network had a total of 34 hours of coverage, with 29 hours on Thursday and Friday, and 5 hours on Saturday and Sunday. The NBC broadcast network had a total of 15 hours of coverage on the weekend, with 8 hours Saturday, and 7 hours Sunday. The 49 total hours of coverage on Golf Channel and NBC is down 30 minutes from 2018; the difference is that NBC’s Sunday coverage is down 30 minutes, from 7.5 hours in 2018, to 7 hours in 2019.

Timeline of U.S. broadcasting rights[edit]

| Period | Broadcaster | Rights fee per annum |

|---|---|---|

| 1962–2009 | ABC | Varies |

| 2010–2015 | ESPN | $25.0m |

| 2016[l] | NBC | $25.0m[l] |

| 2017–2028 | $50.0m |

Ref:[189]

TheOpen.com[edit]

The Open provides limited coverage for free on its website including highlights, featured groups, featured holes, and radio coverage. The Open’s local rights holders usually provide these feeds as part of their broadcast package.[192]

Rest of the world[edit]

The Open produces a ‘world feed’ for use by international broadcasters if they require.[170] The other large golf markets in a similar time zone as the U.K. are the rest of Europe (where Sky, the U.K. broadcast company often has a presence), and South Africa where it is covered by SuperSport.[193]

Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and increasingly China are markets with high media interest in golf and the Open, but the time zone means the prime coverage is shown in the early hours of the morning.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Before 2017 the prize fund was always stated and paid in pound sterling (£). Since 2017 the prize fund has been stated and paid in United states dollar (US$).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Macdonald Smith is classified as American by Open records, but it is noted he was born in

Scotland. He was a naturalised American citizen when he competed in the Open.

Scotland. He was a naturalised American citizen when he competed in the Open. - ^ Tommy Armour is classified as American by Open records, but it is noted he was born in

Scotland. He was a naturalised American citizen when he won. He was nicknamed the “Silver Scot”, and is a member of the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame.[167]

Scotland. He was a naturalised American citizen when he won. He was nicknamed the “Silver Scot”, and is a member of the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame.[167] - ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f As the winner was an amateur, he received no prize money.

- ^ Aubrey Boomer was from

Jersey, a Crown Dependency. Although Jersey is not part of England, the Open records classify him as English.

Jersey, a Crown Dependency. Although Jersey is not part of England, the Open records classify him as English. - ^ Jump up to:a b Jim Barnes is classified as American by Open records, but it is noted he was born in

England. Open records state he was a naturalised American citizen when he won, but the World Golf Hall of Fame notes about Barnes: “He never became an American citizen, remaining an intensely patriotic Cornishman”.[168]

England. Open records state he was a naturalised American citizen when he won, but the World Golf Hall of Fame notes about Barnes: “He never became an American citizen, remaining an intensely patriotic Cornishman”.[168] - ^ Jump up to:a b c Ted Ray was from

Jersey, a Crown Dependency. Although Jersey is not part of England, the Open records classify him as English. He represented England nine times in the England–Scotland Professional Match, and spent most of his life living in England.

Jersey, a Crown Dependency. Although Jersey is not part of England, the Open records classify him as English. He represented England nine times in the England–Scotland Professional Match, and spent most of his life living in England. - ^ Jock Hutchison is classified as American by Open records, but it is noted he was born in

Scotland. Open records state he was a naturalised American citizen when he won.

Scotland. Open records state he was a naturalised American citizen when he won. - ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Harry Vardon was from

Jersey, a Crown Dependency. Although Jersey is not part of England, The Open records classify him as English. He represented England nine times in the England–Scotland Professional Match, and spent most of his life living in England.

Jersey, a Crown Dependency. Although Jersey is not part of England, The Open records classify him as English. He represented England nine times in the England–Scotland Professional Match, and spent most of his life living in England. - ^ Tom Vardon was from

Jersey, a Crown Dependency. Although Jersey is not part of England, the Open records classify him as English. He represented England seven times in the England–Scotland Professional Match, and was a club professional in England.

Jersey, a Crown Dependency. Although Jersey is not part of England, the Open records classify him as English. He represented England seven times in the England–Scotland Professional Match, and was a club professional in England. - ^ Jump up to:a b BBC sold the rights to Sky for £7.0m

- ^ Jump up to:a b ESPN sold the rights to NBC for an undisclosed fee

References[edit]

- ^ “Open Championship to pay winner record $3 million”. ESPN. 12 July 2023. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “The Claret Jug / All You Need To Know”. The Open. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o “The Open Championship: Champion Golfers Through The Years”. Professional Golfers Career College. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Bradbeer, Richard; Morrison, Ian (2000). The Golf Handbook. Abbeydale Press. ISBN 1-86147-006-1.

- ^ “Challenge Belt”. Fife Herald. 11 October 1861. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 21 December 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Preswick Golf Club”. Links Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1860: The Very First Open”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “The Claret Jug: Explore The History of the Golf Champion Trophy, Better Known As The Claret Jug”. Fairways of Woodside Golf Course. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1860: The Very First Open”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1861”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1863”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ “1864”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ “Format”. MOCGC. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ “1875: Prestwick”. antiquegolfscotland.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ “1889”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “Golfers Who Have Won the British Open”. ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “1892”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1894”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1897”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1884”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “British Golf Ruling on Tourney Practice Will Help Americans”. The Evening Review. East Liverpool, Ohio. 16 March 1926. p. 10.

- ^ “1911”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “Golf Championship – First day’s play – An Irishman leads”. Glasgow Herald. 27 June 1911. pp. 9, 10. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ “1907”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1909”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “The Great Triumvirate and inter-war years”. BBC Sport. 4 July 2004. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ “Month at a Glance”. Golf Illustrated. March 1921. p. 32. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ “The history of how Scotland brought golf to America”. The Scotsman. 7 March 2016. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “How the Ryder Cup was born at Gleneagles”. The Telegraph. 20 September 2014. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1921”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “1925”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “1931”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1923”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1926”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1932”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “The Hogan Mystique, reimagined”. Golf Digest. 12 July 2018. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “Open Rota”. Royal Cinque Ports. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1951”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “Centenary Open Championship: prize money increased”. Glasgow Herald. Scotland. 4 December 1959. p. 12. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “PGA Stats” (PDF). PGA of America. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1953”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1969”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1967”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “Draw for the Open Golf Championship”. The Times. 13 June 1957. p. 3.

- ^ “R&A made bigger ball compulsory”. The Times. 22 January 1974. p. 10.

- ^ Jacobs, Raymond (22 January 1974). “American-size ball compulsory in Open”. Glasgow Herald. p. 4. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ “Manufacturers criticize Open ball decision”. Glasgow Herald. 23 January 1974. p. 4. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ “1966”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ “1980”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ “Tom Watson may be the best U.S.-born links player, but don’t discount Jack and Tiger”. Golf.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “1976”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “Tournament History”. European Tour. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “1999”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “2003”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “2004”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “2000”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “2002”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “2009”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “2015”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “2016”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “Jack: Henrik v. Phil better than Duel in the Sun”. Golf Channel. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “2018”. The Open. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “The Open Championship: Leaderboard”. ESPN. 18 July 2019. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ “The Open cancelled – R&A announces St George’s in Kent to host 149th Championship in 2021”. BBC Sport. 6 April 2020. Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ “What Is Links Golf?”. Golf Monthly. 22 July 2018. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ “6. The Putting Greens”. R&A. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ “Top 10 courses in St Andrews, Fife, Angus and Perthshire”. GolfBreaks. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Norris, Luke (17 July 2018). “The Open Championship 2018: Complete list of previous winners”. Fansided. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ “Tom Watson Says Goodbye To British Open at St. Andrews”. Golf.com. 18 July 2015. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ “Hands that hold the British Open trophy every year”. Fox Sports. 20 July 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ “Q&A with the Claret Jug engraver”. Golf Monthly. 1 July 2008. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ “Darren Clarke / An Open love affair”. The Open. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ “Champion golfer of the year is such a cool title”. National Club Golfer. 16 July 2018. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ “Would you drink out of a jug that has been home to bugs, barbeque sauce, corn and gallons of liquor? What if it were the Claret Jug?”. Golf Week. USA Today. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ “From Prestwick to Muirfield”. BBC. 12 July 2002. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Why it’s called ‘The Open’ and not the ‘British Open'”. theopen.com. 7 April 2017. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Weinman, Sam (20 July 2018). “We have explosive new evidence in the endless “British Open” vs. “Open Championship” debate”. Golf Digest. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ “Carnoustie’s Great Week”. Glasgow Herald. Scotland. 1 June 1931. p. 13. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Belden, Sam (20 July 2017). “Open Championship organizers don’t want anybody calling it ‘The British Open’ anymore and it is causing more confusion than ever”. Business Insider. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ “The Open – History”. PGA Tour. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Costa, Brian (18 July 2017). “Dear American Twits, This Golf Event Is Properly Called ‘The Open'”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.(subscription required)

- ^ Ryan, Shane (14 July 2015). “Americans: It’s okay to call this major “The British Open,” and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise”. Golf Digest. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ “Senior Open – History”. PGA European Tour. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ “Women’s Open drops ‘British’ from title in sponsorship rebrand”. BBC. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ “The Five Open Championships”. MOCGC. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ Andreff, Wladimir (2006). Handbook on the Economics of Sport. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 235, 236. ISBN 978-184-376-608-7. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ “Bobby Jones”. Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ “Golf Majors”. ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ “Which Golf Major Is The Most Prestigious?”. Forbes. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ “USPGA hopes it is winners all round when major moves to May”. The Daily Telegraph. 11 August 2018. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ “Tradition lures Americans abroad”. Clarion-Ledger. 18 July 1995. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Thakur, Pradeep (2010). Golf: Career Money Leaders. India: Lulu Enterprises Ltd. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-557-77530-9. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 22 November 2020.[self-published source?]

- ^ “Exemptions”. The Open. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Qualification”. The Open. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ “Graeme McDowell Among 11 Alternates Added to British Open”. Golf.com. 27 June 2016. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ “Events”. OWGR. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ “World’s top 100 ranked players entered in PGA at Valhalla”. Kentucky.com. 29 July 2014. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “British Open 2018: Frequently Asked Questions”. GolfWorld. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ “Future Men’s Major Championships – dates and venues”. Supersport. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ “How the PGA Tour determines tee times and groupings each week”. GNN. 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ Harig, Bob (5 July 2019). “The Open switches to 3-hole aggregate playoff”. ESPN. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ “Open 2017: Why is the prize money paid in dollars this year instead of pounds?”. The Express. 21 July 2017. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ “Baby, You’re a Rich Man: What Winning Another Major Means for Rory’s Finances”. Golf Digest. 22 July 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g “Here are all the goodies the winner of the Open Championship will take home”. GOLF.com. 23 July 2017. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “Claret Jug”. theopen.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “British Open Championship purse payout percentages and distribution”. Golf News Net. 19 July 2018. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Exemptions”. The Open. 14 January 2019. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ “European Tour Order”. European Tour. 14 January 2019. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ “Qualifying Criteria”. WGC-HSBC Champions. 14 January 2019. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ “2015–16 PGA Tour Player Handbook & Tournament Regulations” (PDF). 5 October 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2016.

- ^ “2014 U.S. Senior Open Entry Form” (PDF). USGA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2014.

- ^ “79th Kitchenaid Senior PGA Championship” (PDF). PGA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ “Senior Open Entry Form” (PDF). European Tour. 14 January 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ “The Open 2015: fourth round – as it happened”. The Guardian. 13 July 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ “Qualifications for Masters Invitation”. Augusta Chronicle. 3 January 2018. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ “Open Championship: How is prize money distributed if amateur Paul Dunne wins?”. Sky Sports. 20 July 2015. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Easdale, Roderick (14 July 2021). “Did You Know There Are Seven Open Championship Trophies to Be Won?”. Golf Monthly. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ “Ryle Memorial Medal” (PDF). Professional Golfers’ Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ^ “Braid Taylor Memorial Medal” (PDF). Professional Golfers’ Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ^ “Tooting Bec Cup” (PDF). Professional Golfers’ Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ^ “Special notes on sports”. The Glasgow Herald. 19 June 1893. p. 9. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ “The Open Golf Championship”. The Times. 10 July 1893. p. 7.

- ^ “The Open Championship: third English course adopted”. Glasgow Herald. 18 November 1907. p. 13. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ “The Open Championship”. The Times. 18 November 1907. p. 12.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Deegan, Jason (12 May 2017). “Major changes: Upgraded Dunluce Links at Royal Portrush ready for The Open in 2019”. Golf Advisor. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Prestwick Golf Club”. PrestwickGC. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ “A short history of Prestwick”. The Open. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Scottish Golf History – Oldest Golf Sites”. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ “St. Andrews, Scotland: See the place where golf was born and Will and Kate fell in love”. USA Today. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

Tiny St. Andrews has a huge reputation, known around the world as the birthplace and royal seat of golf. The chance to play on the world’s oldest course – or at least take in the iconic view of its 18th hole – keeps the town perennially popular among golfing pilgrims

- ^ “St Andrews Old”. Golf Scotland. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Reaske, Trevor (15 July 2015). “Why a British Open at St. Andrews is the best event in golf”. SBNation. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ “The Open 2010: Rory McIlroy equals lowest major round at St Andrews”. The Guardian. Press Association. 15 July 2010. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ “1672 Musselburgh – The Lawyer Golfer”. Scottish Golf History. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ “The Musselburgh Opens”. MOCGC. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ “A short history of Muirfield”. The Open. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ “Muirfield to lose right to host Open after vote against allowing women members”. BBC Sport. 19 May 2016. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ “Change of courses for important events – “Open” switched to St. Andrews”. Glasgow Herald. 19 January 1957. p. 9. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ “Royal St George’s Golf Club Course Review”. Golf Monthly. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ “History of Royal St George’s”. Today’s Golfer. 23 June 2011. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ “7 of Golf’s Most Famous Bunkers”. Golf Monthly. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Royal Liverpool – Cheshire – England”. top100golfcourses. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ “2006 British Open: Woods Leaves Wood in the Bag”. ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ “Royal Cinque Ports – Kent – England”. top100golfcourses. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ “Royal Cinque Ports and The Open Rota”. Royal Cinque Ports. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ “The Golf Championship – Official announcement”. The Times. 14 April 1915. p. 16.

- ^ “Gales and snow – Damage on east coast – Widespread flooding”. The Times. 14 February 1938. p. 12.

- ^ “Golf – The Open and Amateur Championships – New Conditions”. The Times. 12 February 1938. p. 4.

- ^ “Open Golf Championship at Sandwich”. The Times. 24 May 1949. p. 6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Royal Troon (Old) – Ayrshire & Arran – Scotland”. top100golfcourses. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ “The Championships”. The Times. 22 May 1922. p. 22.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Royal Lytham & St Annes – Lancashire – England”. top100golfcourses. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Nichols, Beth Ann (1 August 2018). “Intimidating bunkers still an effective defense at Royal Lytham”. Golfweek. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ “A short history of Prince’s”. The Open. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ “Royal Portrush (Dunluce) – Antrim – Northern Ireland”. top100golfcourses. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ “Royal Birkdale – Lancashire – England”. top100golfcourses. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ “Golf Championships for 1940”. The Times. 21 January 1939. p. 4.

- ^ “Condition of course in Locke’s favor”. Glasgow Herald. 5 July 1954. p. 4. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ “Trump Turnberry (Ailsa) – Ayrshire & Arran – Scotland”. top100golfcourses. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Choma, Russ (11 January 2021). “Pro golf finally cancels Donald Trump”. Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ “Turnberry Statement”. The R&A. 11 January 2021. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ “Royal Liverpool & Royal Troon agree Open hosting duties for 2023 and 2024”. BBC Sport. 7 December 2020. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ “The Open to return to Portrush in 2025”. BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ “The Open: R&A announce Royal Birkdale will return as host of The 154th Open in 2026”. Sky Sport. Archived from the original on 11 July 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ “Notes: Young Tom Morris gets 20 days older”. PGA Tour. 1 August 2006. Archived from the original on 5 August 2006.

- ^ “Did you know number 50”. The Open Championship. Archived from the original on 25 November 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ “The 149th Open cancelled for this year and will return to Sandwich in 2021”. Sky Sports. Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ “Tommy Armour”. Scottish Sports Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ “Jim Barnes”. World Golf Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ “PGA Tour Media – The Open Championship” (PDF). PGA Tour. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kerschbaumer, Ken (21 July 2018). “Live From The Open Championship: 198 Cameras Keep CTV OB on the Move; RF Support Gets a Lift”. SVG News. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ “Recommended mandatory superior cash offer for Sky: Compulsory acquisition of Sky shares”. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ “Live From The Open Championship: A New Era Begins for the R&A”. Sports Video Group. 15 July 2016. Archived from the original on 20 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “NBC Sports Group Kicks Off All-Encompassing Coverage From The 147th Open”. Golf Channel. 16 July 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ “Ivor Robson, voice of The Open, dies; Tiger Woods and golf world pay tribute”. NBC Sports. 17 October 2023. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Gibson, Owen (3 February 2015). “Sky Sports wins rights to show Open Championship golf live from 2017”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Kelley, Brent. “Peter Alliss – Biography of Golfer and Broadcaster Peter Alliss”. Golf.about.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ “Code on Sports and Other Listed and Designated Events” (PDF). Ofcom. March 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 January 2011.

- ^ Reid, Alasdair (23 April 2012). “BBC could lose the Open unless it shows more golf”. The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ Murray, Ewan (14 January 2015). “What would it mean for golf if the BBC lost the Open Championship?”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ “BBC could lose exclusive Open coverage rights as R&A ponders new deal”. The Guardian. 8 January 2015. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rumsby, Ben (3 February 2015). “BBC loses live rights to broadcast The Open Championship to Sky Sports from 2017”. The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ “Don’t miss out on the drama”. NOW TV. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ “Open Championship: Sky wins rights; BBC to show highlights”. BBC Sport. 3 February 2015. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Tappin, Neil (17 July 2017). “Sky Sports Or BBC: Who Covered The Open Better?”. Golf Monthly. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019.